Here’s the (rather long) opening essay from the evolving syllabus for the State of the Art course I am developing at the DePauw University School of Music. The entire document, with a reading list, is here.

Even as we see the Fort Worth Symphony on strike, and difficult labor negotiations underway in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, there are also many smaller groups and individual classically-trained performers doing well, happily engaged in a wide range of creative projects. It seems like a good time to share this essay (which seems to want to become a book) with friends and colleagues, especially since this weekend DePauw is hosting the absolutely amazing 21CMposium.

In this course, we look at the past and the present of life as classically-trained musicians in order to enrich your process of imagining possibilities for your future career. It is part of the ongoing question underlying the entire 21cm curriculum: What can it mean to be a musician in the 21st century?

Is there a classical music crisis?

Many people, including the most widely-read blogger on the future of classical music, Greg Sandow, say yes. Greg’s point of view, his narrative, if you will, is that classical music, once vitally connected to mainstream American culture, has become disconnected from contemporary life and needs to change, and change quickly. Orchestras in Detroit, Indianapolis, Louisville, Minneapolis, St. Paul, and Philadelphia have gone through wrenching labor disputes that ended with the players taking significant and painful salary and benefit cuts. The Philadelphia Orchestra went through bankruptcy organization; the Minnesota Orchestra musicians endured a bitter fifteen-month lockout that led to the resignation of its music director (followed by the resignation of its executive director and a final, triumphant reengagement of the music director). Two years ago, the Atlanta Symphony musicians were locked out and the vitriol in the press, especially the “blogosphere” was astounding. In January, a similar mess played out with the smaller Hartford (CT) Symphony, and resolved itself only after the musicians and the music director (conductor) agreed to substantial pay cuts. And now (September 2016) the musicians of the Fort Worth Symphony are on strike, the Pittsburgh Symphony and its players are in closed-door negotiations, and things are starting to heat up again with the Philadelphia Orchestra as well (the players having denounced management’s initial offer as “regressive”).

The New York City Opera, once a popular a thriving “people’s opera” offering a lower cost and often more adventurous alternative to its Lincoln Center neighbor, the Metropolitan Opera, went out of business in 2013. It was revived in a smaller and more flexible form in January 2016, with most of its performances in the Jazz at Lincoln Center venues on New York’s Columbus Circle, particularly the Rose Theater, rather than its former home, the cavernous David H. Koch Theater in the main Lincoln Center complex. (The Rose Theater has approximately half the number of seats as the Koch.)

Peter Gelb, the general director of the Metropolitan Opera, said during union contract negotiations in 2014 that even that institution–perhaps the most famous opera company in the world, and the largest-budget classical-music institution in the United States– faced possible bankruptcy if its employees didn’t take major cuts in compensation. While a settlement avoiding a strike or lockout was reached (Terry Teachout of the Wall Street Journal, asserting the cuts in compensation the singers, players, and stagehands agreed to were too small, called it Apocalypse Later), the Met’s still-shaky finances have been the subject of much discussion. New York Times business columnist and New Yorker staff writer James Stewart, a DePauw alum and trustee, wrote A Fight at the Opera, a major New Yorker piece examining the situation, in March 2015, which we will read.

How’d this happen? Whose fault is it?

We will see that there are competing narratives. Performers and their supporters blame administrators and boards for ineffective fundraising, poor marketing and counterproductive artistic choices. Administrators and boards blame a changing culture and ever-rising expenses, especially the costs of unionized employees whose salary and health and pension benefits are, they say, unsustainable. The Met’s Peter Gelb, who asked its unions for major cuts, has answered his critics in part by saying, “The problem that we face is a social and cultural problem, and the question is not whether I think I’m doing a good job or not in trying to keep the opera alive. It’s whether I’m doing a good job or not in the face of a cultural and social rejection of opera as an art form.” [emphasis added]

As we will see when we read Jim Stewart’s article, others respond that Gelb, who had little or no experience in opera when he took over the Met, has funded over-priced new productions that don’t attract a large enough paying audience or inspire wealthy patrons to donate enough money. Various commentators have pointed out that other opera companies regularly sell out all their tickets–the Vienna State Opera being one of the most notable. On the other hand, while the Met has 3800 seats, Vienna has 2284; a ticket-sales triumph in Vienna is a disaster in New York. It’s complicated.

There are major orchestras doing very well, including those in Chicago, Cincinnati, and Los Angeles. And there’s new enthusiasm surrounding the orchestras mentioned above as having had strikes or lockouts. Their near-death experiences triggered renewed energy and commitment as key segments of the community realized what they were so close to losing, as news coverage of the labor situations generated much needed publicity for the institutions.

When the San Diego Opera board announced in March 2014 that the organization would be disbanded, the city rallied. A new board was put in place, and the institution was saved (at least for now). (Something similar almost happened with the Green Bay Symphony. When its closure was announced in June 2014, a Facebook Group to Save the Green Bay Symphony was formed; it nevertheless ceased operations in April 2015.)

Smaller groups are flourishing in many cases. Our alumnus and oft-quoted blogger Jon Silpayamanant has documented well over two hundred small opera companies that have been formed since 2001, with nearly all of them still operating. One is the Intimate Opera of Indianapolis, co-founded by another School of Music alum, Amy Elaine Hayes (Steven Linville is her co-executive director). The summer music festival I started in Greencastle in 2005 had its biggest audiences and most successful fundraising season ever this year. The part-time Lafayette Symphony (led by SoM alum Sarah Mummey) is thriving.

Perhaps someday we will look back at this period and say, as Mr. Dickens once wrote, “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”

Chicken Littles? Some commentators, including consultant Drew McManus (who writes the Adaptistration blog), call proponents of the “classical crisis” narrative (like Mr. Sandow) “Chicken Littles.” Mr. Silpayamanant, who in recent years has tried to steer clear of inflammatory “Chicken Little” language, often suggests that that problems with attendance are indeed failures of programming and marketing, asserting that the sort of “cultural and social rejection” Mr. Gelb perceives is actually excuse making (the employees of the Met clearly agreed).

Climate Change Deniers? Additional commentators argue classical music is doing fine overall. When the online magazine Slate published Mark Vanhoenacker’s piece “Requiem: Classical Music in America is Dead,” it was met with cutting responses from William Robin in The New Yorker and Andy Doe at his blog Proper Discord. Not surprisingly, those who suggest all is well with classical music are occasionally compared to climate-change deniers (by a commenter on Greg Sandow’s blog, for example) by those enumerating the struggles mentioned above. Dismissing the folding of the New York City Opera, the Indianapolis Opera cutting its 2013-2014 season by 25%, and the strikes and lockouts and drastic pay cuts as inconsequential while pointing to some successes–isn’t that like saying, sure, it was the hottest summer, glaciers are melting, hurricanes are more intense than ever, sea levels are rising, the water tables in portions of Miami are starting to rise above ground, but heck, there was a lot of snow and record cold temperatures in January, so what’s the problem?

Legacy institutions: the hardest hit. Climate change or ineffective management and marketing, the problems we’ve looked at above have been experienced in the most pronounced way by what are sometimes called the legacy institutions of classical music. These are the large organizations which have existed for decades (some over 100 years); have a large number of full-time employees (both administrative and artistic) who receive health-insurance and other benefits, and many of whom belong to powerful unions that resist any change to the status quo; and in most cases perform in very large concert halls or auditoriums which are increasingly difficult to fill. (As I mentioned above, when the smaller scale, revived version of the New York City Opera performs in the Rose Theater at JALC, they have less than half the number of seats to fill than they did at their former home on the main Lincoln Center campus.)

New model/21cm approaches. While many of the legacy institutions struggle, there are a number of ensembles and individual performers who are doing very well. In this course we refer to them as new model and/or 21cm performers and groups. Particularly well-known are the thriving new-music groups such as Kronos, eighth blackbird, Alarm Will Sound, and the International Contemporary Ensemble. The River Oaks Chamber Orchestra in Houston is frequently cited as a successful model; its repertoire includes more standard classical music. Performing in recent years at DePauw have been the vocal group Roomful of Teeth, the versatile string quartet Ethel, the world-influenced Trio Globo, The King’s Singers (an ever-evolving vocal group), and the innovative cellist Maya Beiser. (We bring these groups here primarily to give students in the School of Music a first-hand experience and an opportunity to interact with cutting-edge, “21cm” performers.)

Blue Oceans. Here’s a fascinating metaphor: when many businesses are compete in the same market for the same customers, it’s like a bloody red ocean filled with sharks fighting over the same carcass. Do something new, something original. Then you have no competition. You create your own market. You find yourself sailing in a pristine blue ocean. (Read more at www.blueoceanstrategy.com.)

21cm success stories seem to embody this blue ocean principle. The majority of the 21cm groups we study have a unique repertoire. On the whole, traditional, mainstream string quartets play the great works from Haydn (the first important composer to write string quartets) up through Bartok, with some occasional new pieces. They compete playing pieces which form an essential part of the canon of Western art music. Who plays the best Beethoven or Brahms or Debussy? There are at least a hundred genuinely excellent groups playing this music. It can be a very red ocean. And the same holds true for solo pianists, for singers, for violinists, etc.

21cm groups, on the other hand, aren’t competing with each other playing the same repertoire. Almost always, they have their own: pieces they have commissioned from composers, or that members of the group have written themselves. Many perform new arrangements or “remixes” of music from non-classical genres.

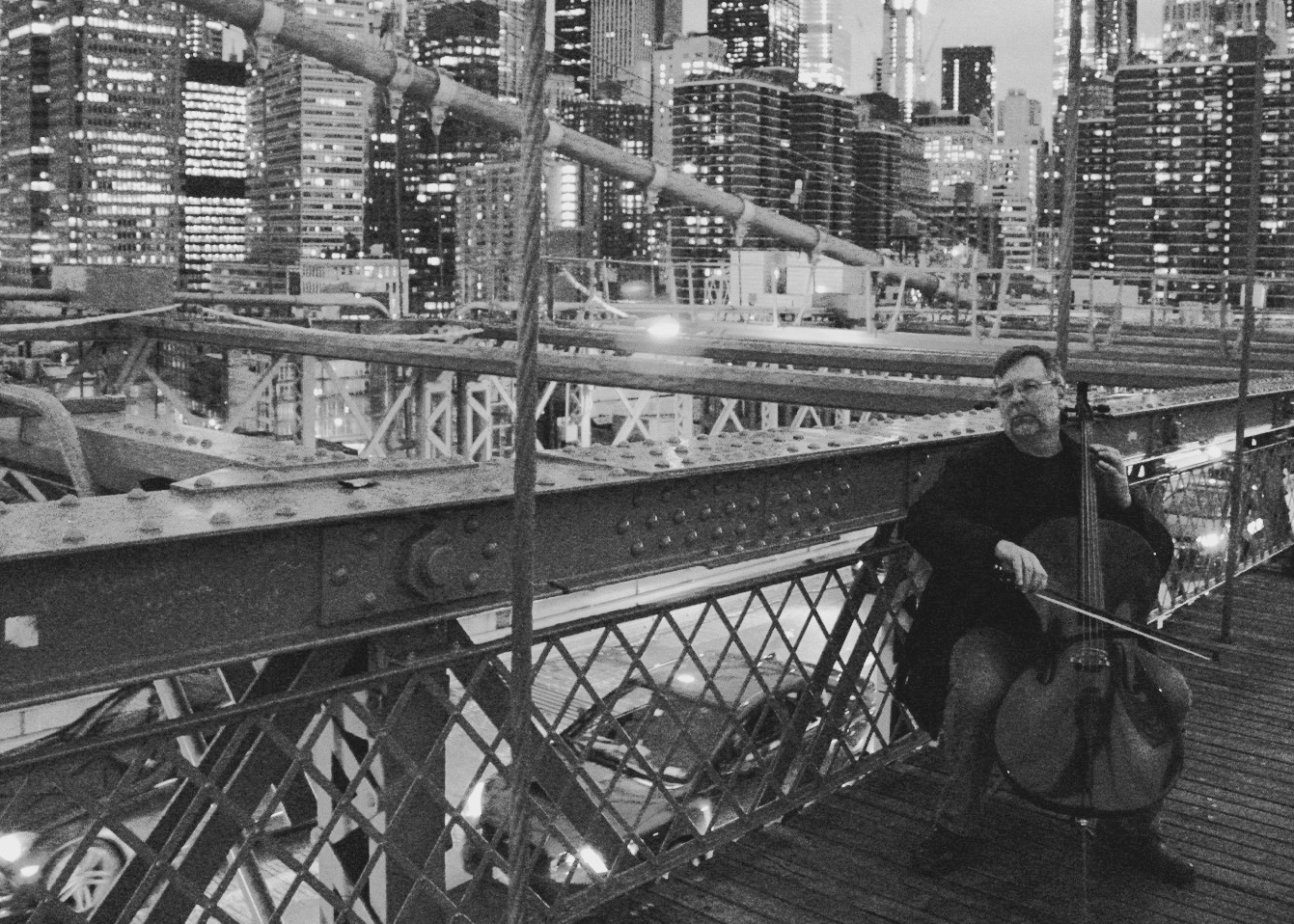

Merging Genres and Intercultural Collaboration and Influence. One thing you’ll notice is that many (although not all) of these groups are deeply involved in combining genres. Time for Three’s virtuoso string players play their own arrangements of Appalachian fiddle music and remix classical standards with a Bluegrass influence; Sybarite5 is famous in part for its Radiohead remixes. The trailblazing cellist Matt Haimovitz, who pioneered playing classical music in rock clubs and bars, has toured with arrangements of songs by Arcade Fire, Radiohead, and others by his performing partner, the pianist Christopher O’Riley (which can be heard on their album Shuffle.Play.Listen.).

Cross-cultural collaboration, fertilization, and mutual influence are frequent as well. Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project has been the most high-profile and well-funded of these efforts; it’s performances and other initiatives bring non-western and classical musicians together in amazing global collaborations. Classical performers who participate in Silk Road, such as the the string quartet Brooklyn Rider and the chamber orchestra The Knights, (of the BR members are core members) have embraced the new eclecticism and broad vision of the Silk Road Project in their own work. In their DePauw concert, Ethel worked with the Native American flutist and composer Robert Mirabal.

Music: It’s Not Just for Concerts Anymore. These 21cm, new-model organizations have also transcended a performance-0nly model (i.e., “we are a music group, we give concerts, and that’s it) to what I first heard the arts consultant and former President of the Kennedy Center Michael Kaiser refer to as the expanded portfolio model. They are deeply involved in education and community-engagement activities and performances in non-traditional venues. “I don’t think of us as a performing organization,” Adrian Ellis, then the executive director of Jazz at Lincoln Center said in a 2011 talk I attended. “We are an educational institution that also presents events.” We’ll see that many of the groups we study, including Fifth House Ensemble and our current ensemble in residence Decoda have educational and community-engagement activities at the core of their work. Decoda’s work in prisons is especially notable, and is definitely the sort of thing that virtually none of your professors thought we were preparing ourselves for when we were in music school.

Alternatives to the Single-Employer Model: Consortiums. In the decades after World War II, symphony orchestras began to pattern themselves on the booming corporate/industrial model of full-time, full-year employment, with unions representing the players, negotiating for increased benefits (such as healthcare and pensions) and better work conditions (a music director can no longer fire a player on a whim, for example, and rehearsals end when scheduled, or the players receive overtime pay). This worked for an increasing number of orchestras for a while (and still does for some), but came at a cost for many players of workplace satisfaction. Players who don’t resonate with a music director and/or section leader’s approach to making music can feel trapped (which is to say that while a lot of full-time orchestra musicians love their jobs, plenty of others are unhappy). To be happy in a full-time orchestra, you have to embrace the fact that other people are going to be deciding what music you’ll play, how it will be interpreted, when the rehearsals and concerts will be, etc. There’s little if any artistic control, which can be deeply frustrating. And as we are seeing, full-year, full-time employment for orchestra musicians is financially unsustainable for an increasing number of institutions.

Meanwhile, more and more groups are working with a consortium model (“an agreement, combination, or group [as of companies] formed to undertake an enterprise beyond the resources of any one member”). Groups such as Fifth House Ensemble, ICE (International Contemporary Ensemble), and Decoda have many member players (10 for Fifth House, 33 for ICE, 32 for Decoda). Often small subsets of the group, two to three musicians, perform a concert or engage with students at a school or inmates in a prison, with the entire group performing together only on special occasions. Here’s how ICE explains it:

ICE projects are by nature modular and malleable. The ensemble is comprised of 33 soloists, among which myriad combinations of instrumental configurations are possible. ICE can be a comprised of a laptop alone on the stage of a nightclub one night; a performance installation in a gallery with three ICE musicians the next night; a large ensemble on stage at Lincoln Center the night after that; and any imaginable combination among, between or beyond.

Portfolio Careers. Relatively few of these new-model/21cm groups are based on the full-time, single-employer model. Instead, most 21cm musicians have portfolio careers, in which they perform with multiple ensembles, play solo concerts, teach privately or through educational institutions, and sometimes even do non-musical work that complements and informs their core artistry. Many musicians thrive on the creative variety and interaction with new collaborators that this career structure embraces, and if they are based in a consortium-model organization, they report that their other experiences enrich their work with the core organization.

The consortium/portfolio career model, with its infinite flexibility and virtually unlimited opportunity for creative growth, is appealing to many musicians who are more attracted to creative control and growth than financial stability. Teaching, through private lessons, workshops, and masterclasses, fits easily into this model as well. Many artists enjoying this kind of career prefer it over a full-time orchestra job. And with full-time jobs becoming fewer, and the long-term health of many legacy institutions at risk, it is important that you are aware of these possibilities as you imagine your own future

In this course we investigate and document these phenomena, at least as much as a single class of undergraduates can in one semester. We look at successes and failures, at old models and new. We look at the competing narratives. We will develop our own meta-narrative(s), bringing to bear as much information about the philosophy, sociology, history and economics of classical music as we can. We are not only artists, we are intellectuals. We are critical thinkers. And we will exercise those skills, as well as our creativity, in this course.

Most importantly, we will will draw on all we explore and learn to imagine powerful new possibilities for the role of musicians in 21st-century society and an inspiring future to energize you as you move through the rest of your time at DePauw.